Frog Pond Plop

|

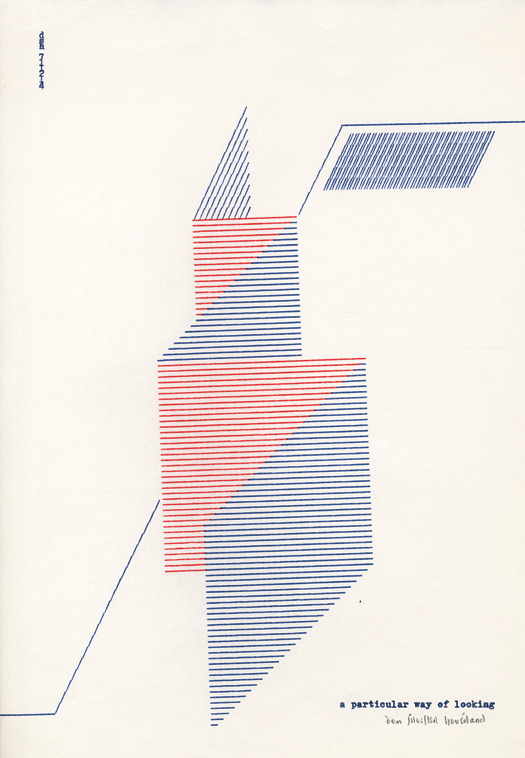

Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter

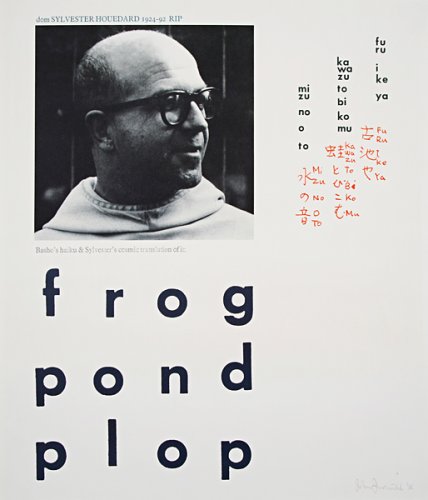

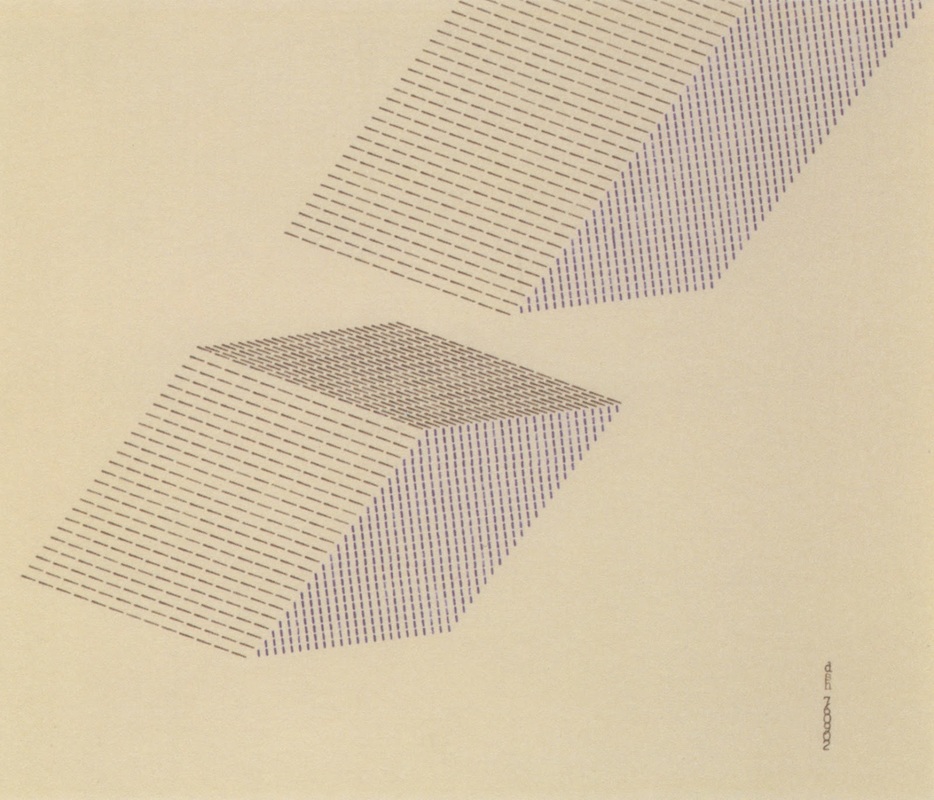

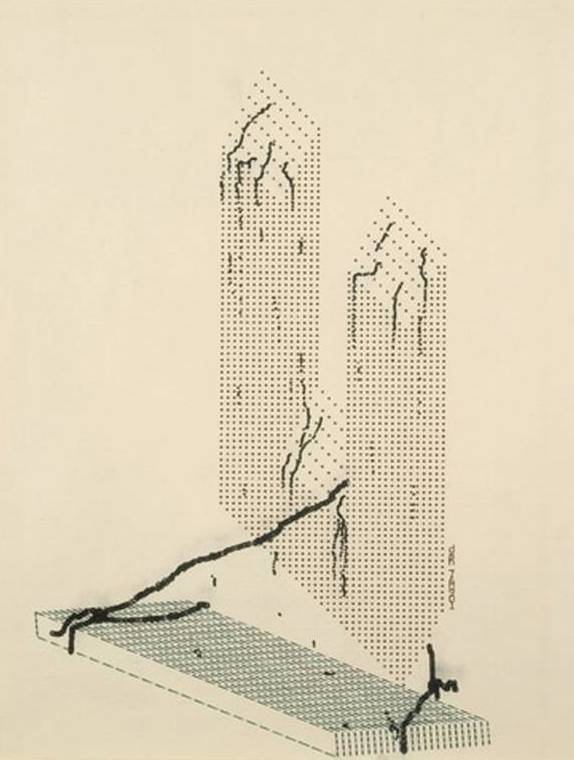

The Life and Work of Dom Sylvester Houedard Edited by Nicola Simpson Occasional Papers UK Dom Sylvester Houedard was one of the earliest exponents of what we now call concrete poetry. He was also a typewriter artist, a spiritual philosopher and a creator of sound poems. The Dom in his name is his title as a Benedictine monk. He usually signed his work ‘dsh’. Among his most famous works is his reduction of Basho’s haiku: Into the ancient pond / a frog jumps / waters sound. Nicola Simpson devotes several pages to this little masterpiece at one point raising the ideas expressed by Houedard that a concrete poem is ‘I-less, Ego-less self effacing, not mimetic’. There is a strong element of truth there. Concrete poems don’t seem to be about me-and-what-I’m-feeling at, for example, my grandmother’s funeral. They tend to be more abstract. I can imagine one about grandmothers in general, but not a specific grandmother. I can imagine one about funerals in general but not a specific funeral. There is much balm in this. I find poems about the topic ‘me-as-poet’ less interesting than poems about the world beyond the poet. So, fortunately, I’ve been spared encountering a design on a page about ‘me-as-concrete-poet’. She also reports: When Houedard presents a variation of frog pond plop as a mini-poster poem for the Brighton Festival in 1967, this co-existential overspill into Buddhist philosophy, particularly Zen, is made more playfully explicit: In enlarging and making bold the letter O in each of the words ‘frog’, ‘pond’, and ‘plop’ it is not just each word of the poem that functions as an abstract painting but now a single letter has become an abstract painting. Constructed like this the letter O is an enso, a Zen circle, both kinetic and contemplative, forcing the reader to cross the border & enter into the poem. Some readers may feel there is a bit of over intellectualising or over analysing going on in some of the essays in this book. There is always the chance of reading too deep a meaning into anything – especially things created by the highly intellectual and spiritual creative force that Houedard was. I like the idea that there is, at base, something playful going on; something light and joyful provided by the pleasant chance of the English language wherein, say, 'toad splashes in puddle', can be rendered more profoundly in three simple sonic and visually harmonic words. While you may enjoy frog pond plop for its surface fun, Nicola Simpson’s essay can take you into subtleties beneath the surface ripples. Frog pond plop may just lodge in your head right beside the red wheelbarrow! Typestracts From the time the typewriter was invented people had been playing around with making pictures using the letters much like dots were used in reproducing photographs in newspapers. Sometime around the 1960’s some more artistically and poetically inclined people started doing artistic things that were a little more sophisticated. A couple of people worth looking up for this (if you haven’t already done so) are Bob Cobbing and Alan Riddell. Houedard’s work in this genre is extremely satisfying and best illustrated by a few examples. He calls them typestracts. The ‘i’ and ‘u’ are from a series called for the 5 vowels. I do like the refreshing perspective looking down at the ‘i’ and the escaping ‘u’ also seems inspired. I find a particular way of looking especially entrancing as well as self-defining. It is difficult not to be impressed with the time and meticulous effort involved in producing this work and so many others that he did. Single copies only – no photocopiers back then. Taking the paper out and turning it this way and that to get the angle as you want it; using different coloured ribbons; using the strictly linear typewriter process to create something that seems if not fluid then certainly concertinaed and opening and expanding and pointing the way up out of the page. I’m sure the same shape and colour patterns created simply in a hand drawing or produced today using a computer drawing program would not have anything like the same effect. What makes these designs beautiful for me is the knowledge of the difficulty of getting them right and the desire to use a tool, the typewriter, in a way unlikely to have been imagined or foreseen by their inventors. It is the stretching of the envelope factor that grabs me by the poetic curlies! Not everything he designs grabs me. I’m afraid that for the most part the collages leave me perplexed. Others may enjoy them more than I do and see things there that I cannot. A further feature of Houedard’s creative output is the sound poem. The Dom was clearly obsessed with the syllable as a sound unit. An essay by David Toop entitled Language and Paralanguage of the Sacred examines the role of chants in religions world wide. Obviously Houedard would have been exposed to religious chanting. It makes sense that a creative force that focused on the margins of the visual and verbal would also take an interest in using the sounds of words and syllables for a poetic effect beyond the literal. Several examples are given of his word scores. Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter contains many examples of Houedard’s work but is nowhere near a ‘collected works’. However there are so many more examples on the internet. Just look up the images under his name and a cornucopia awaits you. A short notice like this cannot do justice to all aspects of this book which is, sadly, unlikely to be found in any Australian bookshop but is easy to buy over the ether. It will probably cost around $50/$60 flown to your door and is worth every cent. |